60 years after she was first published, the fight continues against the silencing of this Black female writer from the favela”.

By Caê Vasconcelos and Maria Teresa Cruz

March, 14th, 1914. This was the day when Carolina Maria de Jesus was born. The writer won the world with her book Quarto de despejo: Diário de uma Favelada (published in English as Child of the Dark: The Diary of Carolina Maria de Jesus) She died in 1977, but still has a large number of unpublished works.

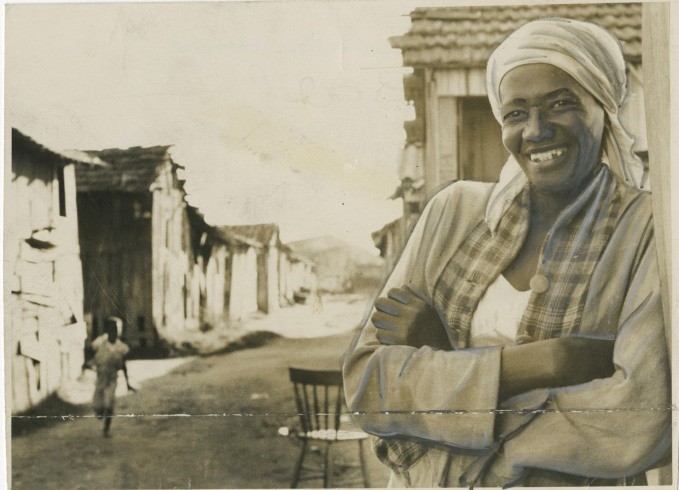

She was a Black woman who lived at the Canindé favela, an extinct community in São Paulo’s north side. But was she born in the small rural town of Sacramento, in the state of Minas Gerais.

March 14th, her birthday, would also leave a mark, many years later in another Black woman’s life, who shared many similar characteristics with the writer: Marielle Franco, a Black and socialist councilwoman, who was murdered on that same day, for daring to be herself.. Carolina was just as daring. With courage, both of them made their mark in the history of Brazil’s Black resistance.

Carolina was unjustly arrested twice., The first time, she was accused of witchcraft by the police for reading books about spiritism. After her second arrest, when she was accused of stealing money from a priest, the writer went from Minas Gerais to São Paulo on foot.

She arrived in São Paulo while the city was growing and becoming modern, seeing the appearance of its first favelas. She built her shack and started living in the Canindé favela in 1947. She used to work scavenging for paper to make a living for herself and her three children who she raised alone.

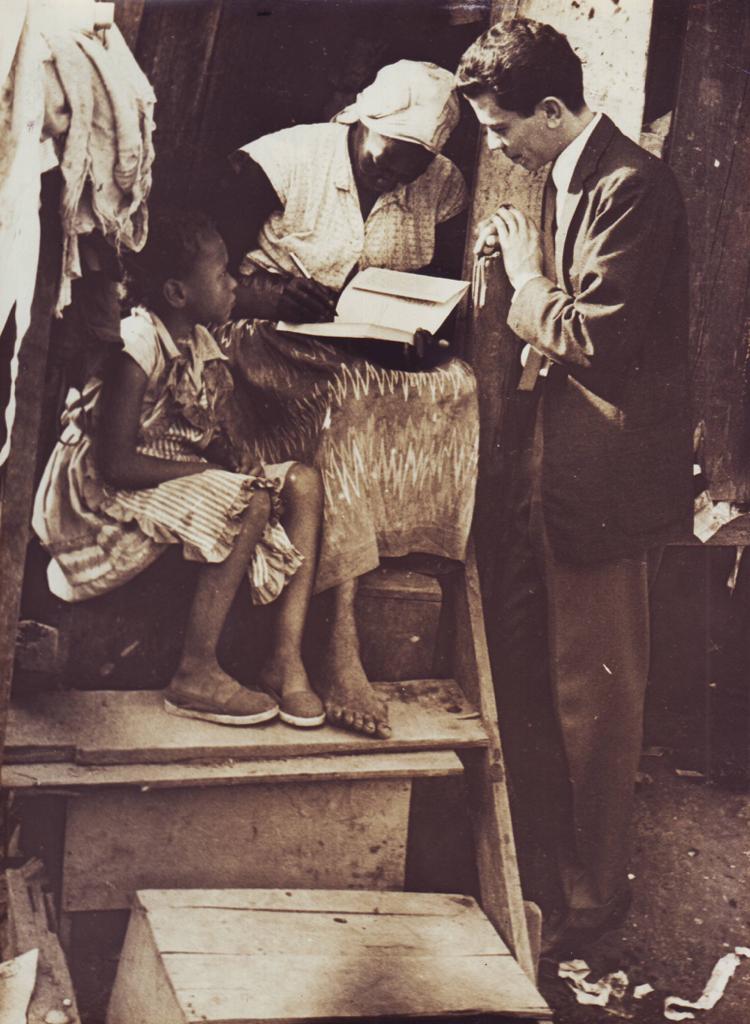

Carolina de Jesus became famous after meeting the journalist Audálio Dantas in 1958. At the time, he was working at the newspaper Folha da Manhã and published a story about her, which achieved great acclaim. In 1960, the journalist helped her publish her first book, Quarto de despejo: Diário de uma Favelada (published in English as Child of the Dark: The Diary of Carolina Maria de Jesus). In a few months, the book sold 100,000 copies and was translated into 15 languages. With the money she earned, she left the favela and moved to a house in the Santana neighbourhood, also in São Paulo’s north side.

Her unpublished works go far beyond the diaries. There are novels, poems, proverbs and plays that are still waiting for the opportunity to reach the public.

In her lifetime, she published four books. In 1961, Casa de Alvenaria: Diários de uma ex-favelada (Cement House: Diaries of a Former Favela Inhabitant), and two years later, Pedaços de Fome (Pieces of Hunger) and Provérbios (Proverbs)

In 1969, she moved to a small ranch in Parelheiros, a mainly rural district in the outskirts of the city of São Paulo, where she spent the rest of her life. After her passing, other five books were published. Yet many of her novels remain unpublished.

In an interview with Ponte, professor Vera Eunice de Jesus Lima, the 66 year old daughter of Carolina de Jesus, tells us that her mother didn’t want to be remembered for her diaries and that she is still, to this day, discovering who her mother really was.

“I lived with my mother for 22 years and sometimes it seems like I never really knew her. I always ask myself: “Who was this woman, for the love of God?”, she jokes. “She had an unique intelligence. Like Audálio Dantas used to say, there will never be another Carolina Maria de Jesus”

Vera also told Ponte that she’s after her mother’s unpublished writings. “My quest today is to set up her collection, to gather everything in one place. I want people to see, to have access, to know who Carolina Maria de Jesus was. I don’t want her things in a drawer”, she added.

The task of carrying Carolina de Jesus’ legacy around the world was given to Vera by her mother herself. On her deathbed, she asked her daughter to prevent her from disappearing. Vera also used to proofread her mother’s texts when she was a child.

“When my mother died, she gave me a letter where she asked me to spread her name, not let her die. She specifically asked me to look for books that were scattered around Brazil with other people”, she says.

The professor talks about her mother with longing and admiration. “Even though we had stretches when we didn’t have anything to eat, she was always there, looking to teach us, to improve our culture. She taught me how to read. She always brought us art, music; we used to play the guitar and sing together”, she recalls.

“She represents the silencing of Black women”

Researcher Fernanda Rodrigues de Miranda, 34, who has a PhD in Literature from São Paulo University (Universidade de São Paulo – USP), studied the work of Carolina for her masters thesis. She points that the book Pedaços de Fome (Pieces of Hunger), published in 1963, is the third novel by a Black woman published in Brazil.

“Before that, we had one by Marina Firmina dos Reis and one by Ruth Guimarães”, she says.

Even though Rodrigues studied the author for more than seven years, she states that it is hard to say who Carolina really was. “The complexity of her works”, Fernanda ponders, “cannot be put in a single box.”

“She became well known and was stereotyped as the ‘favela woman who writes’. But her writing and her literary project are multilayered”.

“Carolina was ironic, playful and extremely sarcastic. Her writing was very lyrical and poetic. Some features of her writing remain subdued because she was always restrained by this favela woman who writes character, instead of an author in her own terms”.

For the researcher, even today, 43 years after her death, Carolina de Jesus still suffers from the erasure that systemically affects the voices of Black women.

“We can think of Carolina in the context of the Black woman who suffered prejudice from all sides, at all levels, and in every sense, and who, even today, has not had her literary project known and recognized”.

“We still don’t really know all of Carolina’s writings, which are numerous. She wrote six or seven novels which are still not published. If these novels were to come out, it could start changing the minority condition in terms of the quantity of published works by Black women,” Miranda points out.

It is impossible to talk about Audálio without mentioning Carolina and vice versa

Journalist Vanira Kunc, 62, recalls the story of Carolina de Jesus through the eyes of her husband Audálio Dantas, who passed away on May 30, 2018. Vanira tells Ponte that she became acquainted with the writer while she was alive, but became very close to her daughter, Vera Eunice. “I fell in love first with Vera and then with Carolina,” she confesses.

Many originals of Carolina de Jesus remained with Audálio and are now with Vanira. “Audálio donated to the National Library from conversations to originals. He gave many interviews and lectures to talk about how it was to live with Carolina”.

Audálio Dantas met Carolina de Jesus while on assignment as a reporter at the Canindé favela to write a story. When he got there, he heard Carolina talking about a book she was writing.

“[The famous Brazilian writer] Conceição Evaristo once said: ‘Audálio didn’t discover Carolina, Carolina showed herself to Audálio’,” recalls the journalist.

Carolina in comics and schools

João Pinheiro, illustrator and screenwriter, learned about Child of the Dark while watching a TV program about rap, when a singer mentioned her name. He wrote it down, bought it, read it, and shared the book with his wife, teacher and researcher Sirlene Barbosa. The dream of turning Carolina’s story into a comic book was born, to expand the reach of her work.

“In that context, after the coup in 1964 [the beginning of the period of military dictatorship in Brazil that would continue until the 1980s], a Black writer, from the favela, who denounced all the evils of society within the context of a military government did not go down well. They wouldn’t want to show a reality that wasn’t consistent with what they preached, namely that the country had racial equality, that it was a country that was improving economically. So it was a nuisance,” explains João Pinheiro. “And there’s also the issue with academia, which is white and doesn’t consider Carolina’s importance,” he says.

The book Carolina, published by Veneta, won the special award at the Angoulême Comics Festival, the world’s most important award for the genre in 2019. They hope that the publication will help Carolina reach more and more people, especially teachers and the youth.

“[In 2013] I did a survey with 40 teachers, teachers of reading rooms in the Itaquera neighbourhood [a region where Sirlene also works] and of those, five had heard of her, and about two had just started reading her book” she recalls. “So, if our book helps more people to learn about Carolina, I will have reached my goal.”

To Sirlene it is very important that the book also reaches the classrooms. She says that after giving a class about Carolina, one of her students from a special class for adults who have not finished their studies confessed that Carolina had inspired her to leave her abusive husband.

For João Pinheiro, overcoming is the word that best defines Carolina’s work. “Her story is very sad, very heavy. But at the same time, she has a lot of strength. So, despite having this misery, hunger, the degrading situation that she lived in, on the other hand she has a lot of strength and persistence. And she overcomes everything, even in the face of those difficulties, she manages to move on, to get up every day and not to give up”, he says.

Translation: Pedro Ribeiro Nogueira | Proofreading: Juan Carlos Urbina

[…] um desses pontos, os organizadores contam histórias de personagens negros, como Luiz Gama e Carolina Maria de Jesus, e conta sobre a importância dos locais para a história […]

[…] a capital paulista — a escritora escreveu poemas, romances, provérbios e peças teatrais ainda não publicadas —, foi a partir das vivências na comunidade paulistana que ela se inspirou a escrever Quarto […]